The Dark Side of Japan’s Work Culture

Last updated: December 08, 2025 Read in fullscreen view

- 01 Sep 2022

Facts Chart: Why Do Software Projects Fail? 29/596

Facts Chart: Why Do Software Projects Fail? 29/596 - 21 Nov 2025

The Pressure of Short-Term Funding on Small-Budget IT Projects 25/35

The Pressure of Short-Term Funding on Small-Budget IT Projects 25/35 - 18 Dec 2025

AI: Act Now or Wait Until You’re “Ready”? 22/42

AI: Act Now or Wait Until You’re “Ready”? 22/42 - 03 Dec 2025

IT Outsourcing Solutions Explained: What, How, Why, When 18/40

IT Outsourcing Solutions Explained: What, How, Why, When 18/40 - 16 Apr 2021

Insightful Business Technology Consulting at TIGO 18/412

Insightful Business Technology Consulting at TIGO 18/412 - 08 Nov 2022

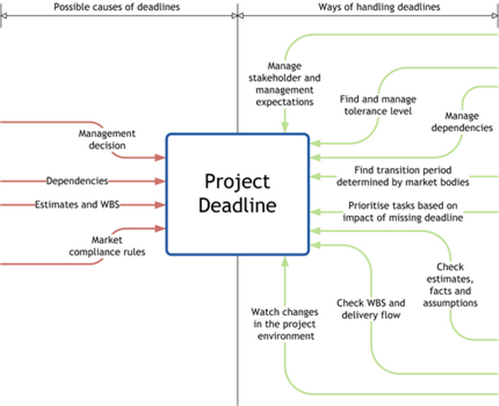

4 tips for meeting tough deadlines when outsourcing projects to software vendor 14/291

4 tips for meeting tough deadlines when outsourcing projects to software vendor 14/291 - 07 Aug 2022

Things to Consider When Choosing a Technology Partner 14/283

Things to Consider When Choosing a Technology Partner 14/283 - 10 Jul 2025

Building AI-Driven Knowledge Graphs from Unstructured Data 14/162

Building AI-Driven Knowledge Graphs from Unstructured Data 14/162 - 07 Jul 2021

The 5 Levels of IT Help Desk Support 13/448

The 5 Levels of IT Help Desk Support 13/448 - 10 Apr 2021

RFP vs POC: Why the proof of concept is replacing the request for proposal 12/322

RFP vs POC: Why the proof of concept is replacing the request for proposal 12/322 - 06 Mar 2021

4 things you need to do before getting an accurate quote for your software development 11/679

4 things you need to do before getting an accurate quote for your software development 11/679 - 03 Nov 2022

Top questions and answers you must know before ask for software outsourcing 11/292

Top questions and answers you must know before ask for software outsourcing 11/292 - 16 Feb 2021

Choose Outsourcing for Your Non Disclosure Agreement (NDA) 11/173

Choose Outsourcing for Your Non Disclosure Agreement (NDA) 11/173 - 01 Nov 2025

From Miracle to Mirage: The Truth Behind “Vibe Coding” 10/51

From Miracle to Mirage: The Truth Behind “Vibe Coding” 10/51 - 01 Jul 2025

Southeast Asia Faces a Surge of “Fake AI Startups” 8/84

Southeast Asia Faces a Surge of “Fake AI Startups” 8/84 - 09 Jan 2022

How to Bridge the Gap Between Business and IT? 8/178

How to Bridge the Gap Between Business and IT? 8/178 - 09 Mar 2022

Consultant Implementation Pricing 8/213

Consultant Implementation Pricing 8/213 - 01 Mar 2023

How do you deal with disputes and conflicts that may arise during a software consulting project? 7/165

How do you deal with disputes and conflicts that may arise during a software consulting project? 7/165 - 13 Oct 2025

Why Fiverr’s Freelance Empire Self-Destructed 7/65

Why Fiverr’s Freelance Empire Self-Destructed 7/65 - 07 Oct 2022

Digital Transformation: Become a Technology Powerhouse 6/244

Digital Transformation: Become a Technology Powerhouse 6/244 - 01 May 2023

CTO Interview Questions 5/329

CTO Interview Questions 5/329 - 09 Feb 2023

The Challenge of Fixed-Bid Software Projects 5/213

The Challenge of Fixed-Bid Software Projects 5/213 - 20 Nov 2022

Software Requirements Are A Communication Problem 5/244

Software Requirements Are A Communication Problem 5/244 - 30 Oct 2022

How Much Does MVP Development Cost in 2023? 5/240

How Much Does MVP Development Cost in 2023? 5/240 - 17 Mar 2025

IT Consultants in Digital Transformation 3/84

IT Consultants in Digital Transformation 3/84

Fearing negative reactions from bosses and colleagues, many Japanese employees are turning to services that resign on their behalf.

Yuujin Watanabe, 24, in Tokyo, works as a “resignation consultant” at Momuri, a company founded in 2022 that helps workers overcome the fear of ending their employment contracts.

For many Japanese people, quitting a job is far more complicated than simply submitting a resignation letter. Pressure to stay, ignored or torn-up resignation letters, fear of retaliation, and strict corporate norms make the process extremely stressful.

“When we reach out, managers at some companies may use harsh language, even insults,” Watanabe said.

The emergence of companies like Momuri since around 2017 highlights the dark side of Japan’s work culture: a rigid hierarchy that gives excessive power to superiors, long hours, and unpaid overtime as the norm.

Taking paid leave is also difficult. A 2023 government survey found that workers use only 62% of the paid vacation days they’re entitled to.

Despite government reforms, change has been slow, allowing the resignation-proxy industry to flourish. Shinji Tanimoto, 35, founder of Momuri, said requests have surged from a few dozen to more than 1,800 per month.

This culture not only strains workers’ physical and mental health, but also contributes to Japan’s demographic crisis, as overwork depresses birth rates. Independent think tank Recruit Works Institute estimated that Japan faced a shortage of 251,000 workers last year, projected to reach 11 million by 2040.

Some companies have begun to change, but many still cling to old practices. “That’s why I believe many people still need resignation-support services,” Tanimoto said.

The roots lie in the postwar economic boom, when the ethos of messhi hoko-self-sacrifice for the group-became entrenched, reinforcing expectations of total dedication. Many companies still hire lifelong “members” rather than for specific roles, giving employers significant control over job assignments.

Ryo Nitta, director of the Japan Work Style Innovation Institute, calls this a “blank contract,” where those who work long hours and comply with all demands are valued, promoted, and then hire similar people.

Designer Kotetsu Genda (name changed), 36, experienced this culture firsthand when he entered the workforce in 2014. At his former company, he and colleagues often stayed until the last train. His boss once suggested he commute by bicycle so he wouldn’t miss it. During peak seasons, workdays stretched until 2–3 a.m., and at times he brought a sleeping bag to the office for an entire week, despite low pay and no overtime compensation.

This harsh work culture can even be deadly-a phenomenon known as karoshi (death from overwork). The death of NHK journalist Miwa Sado in 2013 at age 31 from heart failure after logging 159 hours of overtime in a month is a well-known example. Despite reforms at NHK, another reporter died from karoshi in 2019.

Genda recently moved to a company with better work-life balance. He describes his old reality as shachiku (company livestock). “To me, the line between a ‘salaryman’ and a ‘shachiku’ is blurry,” he said.

To drive change, the government enacted the Work Style Reform Law in 2019, capping overtime at 45 hours per month (up to 100 hours in certain cases), promoting flexible work, and reducing wage disparities.

However, many workers do not assert their rights due to the tradition of shushin koyo (lifetime employment) and fear of losing their jobs. Yuji Kobayashi, a researcher at Persol Research and Consulting, noted that many lack the skills to change jobs and hesitate to speak up for fear of displeasing their superiors.

The result is low engagement. A Gallup study last year found that only 6% of Japanese workers are engaged at work-one of the lowest rates in the world. Labor productivity stands at just USD 56.8 per hour, far behind Ireland, the world leader at about USD 157. This low engagement cost Japan an estimated 86 trillion yen (USD 585 billion) in 2023, about 15% of its GDP.

Recent reform efforts include the Tokyo metropolitan government adopting a four-day workweek for public employees starting April 2025. In the private sector, however, only 8% of companies offered this option as of 2021, and many firms have even scaled back remote work post-pandemic.

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)-over 99% of all businesses-struggle with labor shortages, low productivity, and rising costs. Last year, more than 10,000 companies went bankrupt, mostly SMEs. Kobayashi pointed out that many firms in depopulating regions “are not flexible enough to change.” As a result, SMEs are given more leeway in implementing reforms. For example, 75-year-old Nariaki Asano’s timber company sets work hours flexibly depending on tasks rather than fixed schedules.

Reforms are showing some progress today. The share of public servants working more than 60 hours a week has declined. About 64% of companies say they are working to narrow wage gaps. Average monthly overtime fell to 22.76 hours in 2023, down from 26.79 hours before reforms, according to job platform OpenWork.

Younger workers’ attitudes are also shifting. A survey last year found that the share of those willing to change jobs or start their own business has doubled since 2014, while interest in lifetime employment has fallen. “Focusing on one’s own career and life is becoming increasingly important,” Kobayashi said.

Link copied!

Link copied!

Recently Updated News

Recently Updated News